|

Ojai, California

In 1947 Alan Harkness and colleagues formed the High Valley

Theatre Workshop in the Ojai valley in California. The valley was a

haven for artists, writers, musicians and those in search of

spiritual refuge in a time of chaos. Krishnamurti lived there for

many years, founding a high school with Aldous Huxley and others.

A brochure for the school expresses its aims as

follows;

The aim of The High Valley Theatre is to be a

workshop wherre actors may be fully trained, and a theatre where

significant plays, old and new, may be prepared and sent on

tour, with the actors receiving this necessary experience before

audiences. The training ground is to be a home to which the

actors may return and further develop and deepen the work.

The method of training is based on the

approach of the Chekhov Theatre Studio, whereby a thorough

training of voice and body for dramatic expression, as well as

the actor's own inner creativeness is developed.

Some Important Aspects of the Training:

-

Imagination of a role, inner and outer

characteristics and their incorporation.

-

Approach to technique through

psychological gesture, objective and

justification.

-

The five Greek Gymnastics which form a basis

for many aspects of dramatic expression.

-

Deepening the experience of speech

through studies based on Rudolf Steiner's method of

Speech Formation and Eurythmy.

-

Fencing.

-

Dancing.

-

The application of all points of approach to

dramatic sketches and improvisations,

where problems of atmosphere, ensemble,

rhythm, dramatic form and style are

exercised.

Lectures will be given on theatre history,

evolution of the drama and past and present trends.

Performances: A large part of the training

will consist of public appearances in plays which have been

prepared in the workshop. This will provide opportunity for

practical experience in makeup, and in the preparation of

costumes, scenery and lighting for the

stage.

***

Notes about the aim in our Performances

(from the notebooks of Alan Harkness)

To transform the everyday body so that it may move as the

expression of soul and spirit.

To transform the everyday

speech so that the sounds and rhythms of poetry become vocal and

inevitable

A word has its gesture

A movement has

its sound

A true drama has its form which is gesture -

movement sound - word.

There are studies which lead to

these inner dynamics. When achieved in a performance they make a

strong impression on an audience, even if it does not understand

the actual language of the speech. The deeper levels of the

human being are touched, not only of the head - understanding

and sentiment. With such means one can more faithfully reveal

the human tragi-comedy; awaken the emotions of the audience and

in the Aristotelian sense bring harmony into these

emotions.

We believe that the sustenance given to the

audience psyche by such a performance is of especial value in

our age when so much coarsens and deadens it.

Various

techniques are being worked at to create this expressive

rhythmical theatre and the response of audiences in Italy,

Germany, Switzerland and Paris are encouraging - school children

are particularly enthusiastic; but above all our aims are to

move to tears and laughter; to invoke by the magic of theatre

the unsuspected angels and even demons; and by the sympathetic

participation of the audience to bring about a transformation of

human nature. If only one could achieve it and if one dared say

it: -

the theatre as an act of redemption.

This it certainly was at its

greatest and can become so again today.

***

Notes for an article on The High

Valley Theatre production of Uncle Vanya

- Alan Harkness

As it is with any work of art, different people have

different interpretations of the play, Uncle Vanya. It is

in interesting for those of us actively at work on a production

of the play, here in Ojai, to read the New York critics on the

current Old Vic presentation of the piece, and to note the local

response here to the play. Stark Young, one of the few cultured

and perceptive drama critics writing in New York, defends the

play but criticises the lack of complete faith and mutual

response in the acting of the English company. Of course reality

and ensemble playing were especially developed by the Moscow Art

Theatre where the Chekhov plays were first produced, and the

plays are unthinkable without this weaving life. In reply to the

criticism of 'gloom' he write: "Uncle Vanya

is not gloomy; nothing so intense and inwardly alive could be

dismissed as gloomy. It would also be called by Chekhov with his

sensitive, observant, doctor's mind, a comedy."

Our presentation of the play must seem justified and stand

or fall according to its ability to move and enthral an

audience, and convey the special revelation of art. However a

few words as to our view of the play, and our aims in producing

it may be of interest.

To begin with, we feel privileged

to work on Uncle Vanya in order to exercise out theatre

craft. The plays of Chekhov with their psychological naturalism,

the weaving of atmospheres and the subtly drawn characters

demand a truthful and fine means of expression. Also, The High

Valley Theatre has a small nucleus of actors who wish to work

hard in an endeavour to create performances of excellence. From

this group, Uncle Vanya could be well cast.

All

the Chekhov plays show us that dark period 1890-1904; the

fin-de-siecle, in middle class Russian life. Happily, that epoch

is over, but in all parts of the world people are still living

through the frustrations, hopes and boredoms of the Vanya

characters. Very few have progressed beyond this. Outer technics

have diverted the attention from within to gadgets and jittery

mechanical amusements so that the soul is stunned; but those

sensitive and courageous enough to look within will see with a

certain humour and horror what Chekhov reveals. And here is one

of the educational values in presenting the play: the

objectifying of the feeling soul life. How few languid beauties

are willing to look within, as does Yelena, and admit: "But

as for me - I am a tiresome, futile person .... In music and in

my husband's house and in all love affairs... When I come to

think of it Sonya, I am very, very unhappy! There is no

happiness for me in this world! None!"

But Chekhov

is not all dejection. The Russian has abundant, vivid life and

humour, and, although he has great difficulty in establishing

any human balance between excesses of exaltation and despair, he

has a religious belief in a future transformed humanity.

Tolstoy, Dostoyevsky, Chekhov and Gorki all give expression to

this. I do not believe this is a wishful thinking born out of

dreadful social conditions, but a deep presentiment of a future

development which may stem from this difficult but wonderful

people.

In Uncle Vanya this belief is shown through

the country doctor, Astrov, who is aware of this meanness of the

contemporary life and of his own deadening feelings, and yet

plants forests for a future race. Regarded as a crank by his

contemporaries for his ideals and his refusal to eat meat, he is

surely a portrayal of the country doctor Anton Chekhov himself.

The last act is a remarkable texture of evening atmosphere and

frustrated lives, with the bells of departing carriages jingling

out into the night, carrying away the loved ones. But the play

ends with a striking scene of belief in the future. Out of a

broken heart, Sonya speaks to the sad Vanya words that glow with

belief, while 'Waffles' strums a guitar.

Two

catastrophic wars have shaken the world since Anton Chekhov

wrote. People at all awake to the times are facing deeper

abysses and seeking further illumination than the diagnosis and

artistry of the doctor-writer could reveal. But as social

history, Uncle Vanya shows us a dark epoch that is over

and that had no answer or solution for the suffering humanity

which Chekhov lays bare with acute sharpness and tender humour.

As theatre, the play awakens fear and compassion and in the

Aristotelian sense leads to a catharsis, also revealing that

which art alone can reveal.

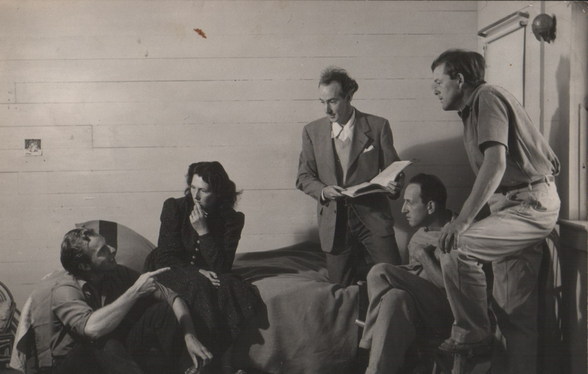

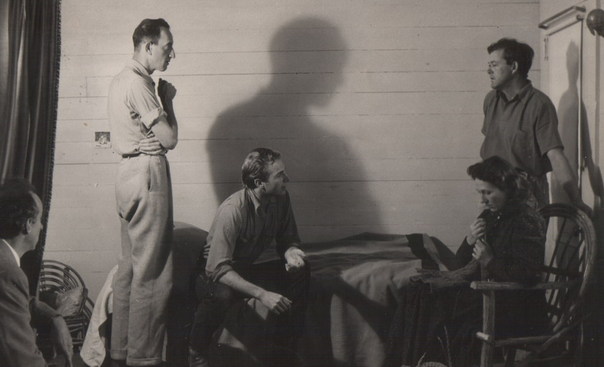

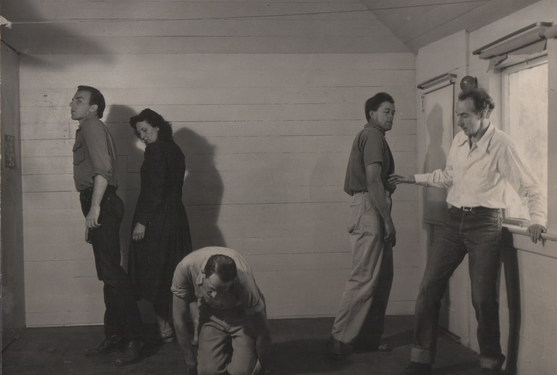

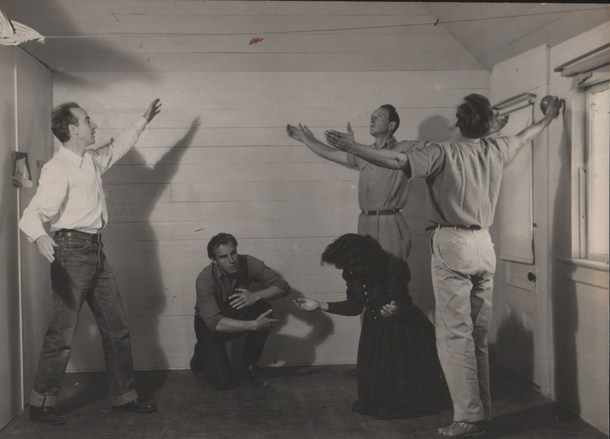

High Valley Theatre - in rehearsal

***

|

|